We’re Already Dwelling within the Metaverse

[ad_1]

“Do a Dance”

The development began, as so many do, on TikTok. Amazon prospects, watching packages arrive by way of Ring doorbell gadgets, requested the folks making the deliveries to bounce for the digital camera. The employees—drivers for “Earth’s most customer-centric firm” and subsequently extremely weak to buyer rankings—complied. The Ring house owners posted the movies. “I stated bust a dance transfer for the digital camera and he did it!” learn one caption, as an nameless laborer shimmied, listlessly. One other buyer wrote her request in chalk on the trail main as much as her door. DO A DANCE, the bottom ordered, accompanied by a contented face and the phrase SMILE. The motive force did as instructed. His command efficiency obtained greater than 1.3 million likes.

Watching that video, I did what I typically do when taking within the information today: I stared in disbelief, briefly puzzled about the distinction between the dystopian and the merely bizarre, and went about my enterprise. However I stored excited about these clips, posted by prospects who noticed themselves as administrators and populated by individuals who, in the middle of doing one job, had been stage-managed into one other.

Dystopias typically share a standard function: Amusement, of their skewed worlds, turns into a technique of captivity fairly than escape. George Orwell’s 1984 had the telescreen, a Ring-like system that surveilled and broadcast on the similar time. The totalitarian regime of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 burned books, but inspired the watching of tv. Aldous Huxley’s Courageous New World described the “feelies”—motion pictures that, embracing the tactile in addition to the visible, have been “way more actual than actuality.” In 1992, Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi novel Snow Crash imagined a type of digital leisure so immersive that it could permit folks, primarily, to dwell inside it. He named it the metaverse.

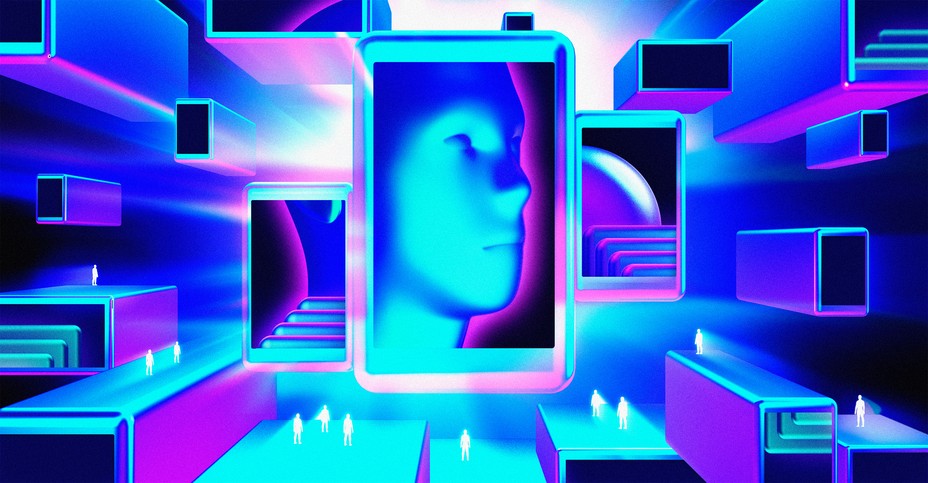

Within the years since, the metaverse has leaped from science fiction and into our lives. Microsoft, Alibaba, and ByteDance, the father or mother firm of TikTok, have all made important investments in digital and augmented actuality. Their approaches range, however their purpose is similar: to remodel leisure from one thing we select, channel by channel or stream by stream or feed by feed, into one thing we inhabit. Within the metaverse, the promise goes, we’ll lastly be capable to do what science fiction foretold: dwell inside our illusions.

No firm has positioned an even bigger guess on this future than Mark Zuckerberg’s. In October 2021, he rebranded Fb as Meta to plant a flag on this notional panorama. For its new brand, the corporate redesigned the infinity image, all twists with no finish. The selection was apt: The aspiration of the renamed firm is to engineer a type of endlessness. Why have mere customers when you possibly can have residents?

For now, Meta’s promise of immersive leisure appears as clunky because the goggles required to entry all that limitless enjoyable. However the promise can be redundant: Zuckerberg positions himself as an innovator, however the surroundings that Meta is advertising and marketing already exists. The place have been these Amazon drivers doing their dancing, if not within the metaverse?

Sooner or later, the writers warned, we’ll give up ourselves to our leisure. We are going to grow to be so distracted and dazed by our fictions that we’ll lose our sense of what’s actual. We are going to make our escapes so complete that we can’t free ourselves from them. The end result might be a populace that forgets assume, empathize with each other, even govern and be ruled.

That future has already arrived. We dwell our lives, willingly or not, inside the metaverse.

A Vaster Wasteland

When students warn of america turning into a “post-truth” society, they sometimes concentrate on the ills that poison our politics: the misinformation, the distrust, the president who apparently thought he might edit a hurricane with a Sharpie. However the encroachments of a post-truth world are issues of tradition as nicely.

In 1961, Newton Minow, simply appointed by President John F. Kennedy to steer the Federal Communications Fee, gave a speech earlier than a convocation of TV-industry leaders. He was blunt. The executives, he stated, have been filling the air with “a procession of sport exhibits, formulation comedies about completely unbelievable households, blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, homicide, Western unhealthy males, Western good males, personal eyes, gangsters, extra violence, and cartoons.” They have been turning TV into “an enormous wasteland.”

The epithet caught. Minow’s speech is greatest remembered for its criticism of TV, but it surely was additionally a prescient acknowledgment of the medium’s energy. TV beamed its illusions into dwelling after dwelling, mind after mind. It formed folks’s views of the world even because it distracted them from actuality.

Minow made his speech in an period when tv was contained to 3 broadcast channels, to sure hours of the day, and, for that matter, to the lounge. Immediately, in fact, screens are all over the place; the leisure surroundings is so huge, you will get misplaced in it. Once we end one sequence, the streaming platforms humbly recommend what we’d like subsequent. When the algorithm will get it proper, we binge, disappearing right into a fictional world for hours and even days at a time, much less sofa potato than lotus-eater.

Social media, in the meantime, beckons from the identical gadgets with its personal guarantees of limitless leisure. Instagram customers peer into the lives of pals and celebrities alike, and submit their very own touched-up, filtered story for others to eat. TikTok’s limitless expertise present is so fascinating that members of the intelligence neighborhood worry China might use the platform to spy on People or to disseminate propaganda—feelies as a weapon of conflict. Even the much less photogenic Twitter invitations customers to enter an alternate realm. As the New York Instances columnist Ross Douthat has noticed, “It’s a spot the place folks type communities and alliances, nurture friendships and sexual relationships, yell and flirt, cheer and pray.” It’s “a spot folks don’t simply go to however inhabit.”

I’ve inhabited Twitter in that approach too—simply as I’ve inhabited Instagram and Hulu and Netflix. I don’t need to query the worth of leisure itself—that might be silly and, in my case, deeply hypocritical. However I do need to query the maintain that all the immersive amusement is gaining over my life, and perhaps yours.

Dwell on this surroundings lengthy sufficient, and it turns into tough to course of the details of the world by way of something besides leisure. We’ve grow to be so accustomed to its heightened environment that the plain outdated actual model of issues begins to look boring by comparability. A climate app just lately despatched me a push notification providing to inform me about “fascinating storms.” I didn’t know I wanted my storms to be fascinating. Or take into account an e-mail I obtained from TurboTax. It knowledgeable me, cheerily, that “we’ve pulled collectively this 12 months’s greatest tax moments and created your personal personalised tax story.” Right here was the leisure crucial at its most absurd: Even my Type 1040 comes with a spotlight reel.

Such examples could appear trivial, innocent—manufacturers being manufacturers. However every invitation to be entertained reinforces an impulse: to hunt diversion at any time when doable, to keep away from tedium in any respect prices, to privilege the dramatized model of occasions over the precise one. To dwell within the metaverse is to count on that life ought to play out because it does on our screens. And the stakes are something however trivial. Within the metaverse, it isn’t surprising however fully becoming {that a} game-show host and Twitter character would grow to be president of america.

Within the years since Minow delivered his speech, the language of tv has come to saturate the way in which People discuss concerning the world round us. People who find themselves deluded, we are saying, have “misplaced the plot”; individuals who have grow to be pariahs have been “canceled.” In earlier ages, folks attributed their circumstances to the need of gods and the whims of destiny; we attribute ours to the inventive selections of “the writers” and lament that we could also be dwelling by way of America’s ultimate season. These are jokes, in fact, however they’ve an uneasy edge. They recommend a creeping realization that we really have come to inhabit our leisure.

Gaslit

Final Could, 19 kids and two of their lecturers have been murdered at Robb Elementary Faculty in Uvalde, Texas. The subsequent day, Quinta Brunson, the creator and star of the ABC sitcom Abbott Elementary, shared a message—certainly one of many—that she’d obtained in response to the bloodbath: a request from a fan that she write a school-shooting story line into her comedy. “Individuals are that deeply faraway from demanding extra from the politicians they’ve elected and are as an alternative demanding ‘leisure,’ ” Brunson wrote on Twitter. “I can’t ask ‘are yall okay’ anymore as a result of the reply is ‘no.’ ”

Brunson’s frustration was comprehensible. But it’s additionally onerous accountable the followers who, as they grieved an actual taking pictures, sought consolation in a fictional one. They’ve been conditioned to count on that the information will instantaneously grow to be leisure.

Virtually as quickly as a giant occasion occurs, a manufacturing firm repurposes it as a pseudo-fiction. In 2019, two Boeing 737 Max airplanes crashed, killing 346 folks; by early 2020, Selection was asserting, “Boeing 737 Max Catastrophe Sequence in Works.” In July 2020, The Hollywood Reporter shared that Adam McKay’s subsequent challenge at HBO would “tackle the timeliest of topics: the race to develop a vaccine for COVID-19.” In January 2021, Reddit customers collaborated to inflate the inventory of the video-game retailer GameStop; every week later, MGM introduced that it had landed the movie rights to a e book proposal—a e book proposal, not an precise e book—concerning the story. Within the metaverse, historical past repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as wry dramedy on HBO Max.

Producers have been ripping plots from the headlines for so long as there have been headlines to tear them from. The distinction as we speak is the velocity and the size of the conversion. There are business causes for this frenzy of optioning. Typically, plundering actuality is way simpler and cheaper than inventing one thing new. The streaming platforms wouldn’t preserve making the sequence, nonetheless, if viewers didn’t watch them. And watching them will be disorienting.

The tagline at first of each episode of Inventing Anna, the 2022 Netflix sequence, neatly sums up the method of the brand new “ripped from the headlines” style: “This complete story is totally true. Apart from all the elements which are completely made up.” Inventing Anna is the lavishly fictionalized story of Anna Sorokin (extra generally recognized by her alias, Anna Delvey), a Russian girl who pretended to be a German heiress to realize the belief after which the cash of wealthy folks in New York Metropolis. It’s a story about lies so brazen that they revealed some well-disguised truths—concerning the magical pondering of excessive finance, about America’s enduring susceptibility to the con artist.

Inventing Anna is predicated on a 2018 New York journal story by the journalist Jessica Pressler. The present weaves the article—lyrically rendered however honestly advised—into its personal model of the story. Inventing Anna is by turns flashy, cheeky, and insightful. It operates within the realm that the postmodernists name hyperreality: Its colours are saturated; its tempo is frenetic; it performs, typically, much less as a drama than as a music video. Most of all, the present sells the concept an unstable relationship between truth and fiction is its personal type of enjoyable.

In that, Inventing Anna is typical. WeCrashed, Tremendous Pumped: The Battle for Uber, The Dropout, and lots of different sequence repurpose high-profile information occasions as shiny amusements. Gaslit, Successful Time, A Pal of the Household, Pam & Tommy, and American Crime Story do related work with historical past so current, it may possibly barely be thought-about historical past in any respect. A lot of them are self-consciously merchandise of “status TV,” and lots of of them are fairly good: neatly written, slickly produced, and carried out by proficient actors.

The exhibits additionally ship a voyeuristic thrill that may be tough for even essentially the most completely reported and artfully advised journalism to rival. The promise of the metaverse has at all times been the flexibility to inhabit realms that might in any other case be closed to us: In a current advert, Meta’s Quest 2 headset transports one younger girl into an NFL scrum and one other into the Ironman go well with. A sequence like The Crown offers the same expertise. We sit with the Royal Household of their bedrooms. We see them combating. We see them weeping. This can be a biopic about lives nonetheless being lived.

In fact, such voyeurism is feasible solely as a result of the exhibits should not sure by the foundations of nonfiction. Like so many entries within the style, The Crown combines finicky photorealism and breezy inventive license. The sequence gives a stitch-by-stitch re-creation of the “revenge costume” that Princess Diana debuted after Prince Charles’s infidelity got here to gentle; it additionally fabricates dialogue, occasions, and whole characters. In 2020, the UK’s tradition secretary requested Netflix so as to add a disclaimer to the present making clear that it’s, essentially, a piece of fiction. Netflix declined, saying it was assured that viewers knew the present was fiction. But its executives absolutely perceive that the sequence is interesting exactly as a result of it presents its fictions with the swagger of settled truth.

One evening this previous fall, my accomplice and I have been watching an episode of Gaslit (concerning the lifetime of the Watergate celeb Martha Mitchell). We have been each side-screening with our telephones, and in some unspecified time in the future we realized we have been doing the very same factor: combing Wikipedia to search out out whether or not the scene we’d simply watched had really occurred. On this, we have been lacking the purpose. Once you’re watching a present like Gaslit or The Crown, you might be supposed to simply accept that the story is true in a broad sense, not a selected one. You aren’t meant to query the distinction between nonfiction and a narrative that’s been “flippantly” fictionalized. And you might be positively not presupposed to be on Wikipedia, making an attempt to cross-reference the true historical past towards the one you’re seeing on Starz.

Right here my TV-loving self interrupts, indignantly and just a little defensively: It’s simply TV. It’s all in good enjoyable. And that’s true. I loved Gaslit. And when Tremendous Pumped forged Uma Thurman as Arianna Huffington and gave her one obvious word—extra camp—I had no selection however to look at. Taken collectively, although, such sequence begin to destabilize our sense of what’s true and what has been invented—or elided—to inform story.

Take into account the Theranos scandal. Elizabeth Holmes’s firm was lined meticulously in actual time by journalists, most prominently at The Wall Road Journal, and the complete arc of her deceptions was described masterfully by the Journal ’s John Carreyrou in his e book, Dangerous Blood. However the fraud has proved so irresistible that it’s now additionally the topic of a documentary, a true-crime podcast referred to as The Dropout, a Hulu drama additionally referred to as The Dropout, and, quickly, an Adam McKay function movie, tailored from Carreyrou’s Dangerous Blood, which can even be referred to as Dangerous Blood. The buyer of all this information and leisure will be forgiven for mixing up the place she obtained her details—and whether or not they’re details in any respect.

In a surreal twist, the fictionalization of the Theranos debacle has now grow to be a part of the nonfiction story line. Final March, the fraud trial of the previous Theranos COO Sunny Balwani was sophisticated when two of the potential jurors who had been chosen to listen to the case have been dismissed; that they had seen episodes of The Dropout and may need been prejudiced by its depiction of the occasions at challenge within the trial.

Within the Nineteen Nineties, media critics frightened—rightly—that the information was turning into frivolous, whether or not within the type of histrionic shoutfests like Crossfire, lurid information magazines like Dateline, or the overheated protection of the O. J. Simpson trial. Then got here a growth in leisure that pretended to be information and to many viewers was indistinguishable from it: Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee. Immediately, the critiques that the information channels have been obsessive about rankings, or that too many individuals had deserted the 6 o’clock information for The Day by day Present, appear quaint. There isn’t a longer any distinction: The information has grow to be leisure, and leisure has grow to be the information.

In January 2021, Britain’s Sky TV introduced that Kenneth Branagh can be starring as Boris Johnson in a miniseries concerning the coronavirus pandemic. Requested concerning the function in September 2022—requested, specifically, concerning the logic of airing a historical past of an occasion that was nonetheless unfolding—Branagh demurred. “I feel these occasions are uncommon,” he stated, “and a part of what we should do is acknowledge them.”

Neither a pandemic that has now killed greater than 200,000 Britons nor a frontrunner who bungled his approach by way of the catastrophe was at risk of going unacknowledged by the BBC or The Instances of London. But Branagh’s remark was telling. The rise of those hyperreal TV exhibits coincides with the decline of the establishments that report on the world as it’s. The semi-fictions stake their claims whereas journalism flails. We now have regularly accommodated ourselves to the concept if an occasion doesn’t grow to be a restricted sequence or a film, it hasn’t occurred. When information breaks, we shrug. We’ll await the miniseries. And take with no consideration that its model of the story might be true—apart from the elements which are completely made up.

The Major Character

By the mid-Twentieth century, the historian Warren Susman argued, an amazing shift was happening. American values had historically emphasised a set of qualities we’d shorthand as “character”: honesty, diligence, an abiding sense of responsibility. The rise of mass media modified these phrases, Susman wrote. Within the media-savvy and consumption-oriented society that People have been constructing, folks got here to worth—and subsequently demand—what Susman referred to as “character”: allure, likability, the expertise to entertain. “The social function demanded of all within the new Tradition of Character was that of a performer,” Susman wrote. “Each American was to grow to be a performing self.”

That demand stays. Now, although, the worth shouldn’t be merely interpersonal allure, however the capacity to broadcast it to mass audiences. Social media has really made every of us a performing self. “All of the world’s a stage” was as soon as a metaphor; as we speak, it’s a boring description of life within the metaverse. Because the journalist Neal Gabler foresaw in his e book Life: The Film, efficiency, as a language but additionally as a price, bleeds into almost each side of expertise.

A current H&M advert marketing campaign promised that the model would ensure that “you’re the fundamental character of every day.” In September, my accomplice booked a lodge room for a weekend journey; the affirmation e-mail vowed that the keep would permit him to “craft your subsequent story.” My iPhone is now within the behavior of reworking images and movies from my digital camera roll into mini-movies. The bespoke movies include a soundtrack chosen by the working system. Additionally they come unprompted: I used to be just lately served up a slideshow, set to strings that Ken Burns may recognize, of images I’d taken of my canine. The purpose, in fact, is business. What higher technique to encourage prospects to be loyal than to inform them their life needs to be a film? A life so full that it will get optioned: the brand new American dream.

Or the brand new American nightmare. On Twitter, “the primary character” is shorthand for the one who might be a given day’s topic of communal scorn. The strangers who pile on, typically with vehemence, could also be reacting to the goal’s reliable failings or merely to perceived ones. Regardless, they could be partaking in what the psychologist John Suler has described as the web disinhibition impact: the tendency for folks in digital areas to behave in methods they by no means would offline. The disinhibition may originate in an assumption that the digital world differs from the “actual” world, or in a way that on-line interactions quantity to a low-stakes sport. However it may possibly lead folks to deal with the people on the opposite aspect of the display screen as not human—not actual—in any respect.

Final July, whereas Lilly Simon was commuting on the subway in New York, a stranger started filming her with out her data or consent. This was when monkeypox, just lately declared a worldwide well being emergency, was spreading within the metropolis. Simon has a genetic situation that causes tumors to develop at her nerve endings; among the growths are seen on her pores and skin. The tumors are normally benign, however can result in painful problems. They aren’t contagious. The particular person recording her knew none of this. As a substitute, the videographer zoomed in on Simon’s legs and arms, analyzing her, and posted the outcomes of their “investigation” on TikTok. Simon, after studying of the video’s existence, posted a reply. “I can’t let any of y’all reverse any years of remedy and therapeutic that I needed to endure to take care of the situation,” she stated in it. Briefly order, her response went viral, the unique video was taken down, and Simon gave an interview concerning the expertise to The New York Instances.

A cheerful ending, of types, to an in any other case grim story of what life will be like within the metaverse: An individual, merely making an attempt to get from one place to a different, is remodeled right into a reluctant star of a film she didn’t know she was in. The dynamics are easy, and stark. The folks on our screens appear like characters, so we start to deal with them like characters. And characters are, in the end, expendable; their goal is to serve the story. When their service is now not required, they are often written off the present.

Rebel for the ’Gram

Disinhibition might start within the on-line world, but it surely doesn’t keep there. The dystopian points of the metaverse tackle a political dimension, although not essentially in the way in which that the Twentieth-century visionaries anticipated. These writers imagined a populace pacified by empty entertainments. They didn’t foresee that the telescreen may as an alternative incite them to political violence.

My colleague Tom Nichols has argued that one of many main motivations driving the January 6 insurrectionists was boredom—and a way that that they had a proper to be the heroes of their very own American Revolution. Definitely, to look at the assault dwell on TV, as I did that day, was to be struck by how most of the folks ransacking the Capitol have been having a grand outdated time. They posed for (incriminating) photographs. They livestreamed their vandalism for his or her followers. They have been doing rebellion for the ’gram. Certainly, a putting variety of the members carried out their sedition dressed as superheroes. A number of tied Trump 2020 flags round their neck, the wrinkled nylon streaking behind them as they plundered.

Some insurrectionists dressed as heroes from one other fictional universe: not Marvel or DC, however QAnon. The origins of the QAnon conspiracy idea are convoluted, and its ongoing attraction has a spread of explanations. However it has thrived, at the least partly, as a result of it’s so nicely suited to the metaverse. Its adherents have filter-bubbled and siloed and red-pilled themselves so utterly that they dwell in a universe of fiction; they belief, above all, within the nameless showrunner who’s writing and directing and producing actuality, each from time to time dropping tantalizing clues about what may occur within the subsequent episode. The hero of the present is Donald Trump, the person who has mastered, like maybe nobody else in American historical past, TV’s powers of manipulation. Its villains are the members of the “deep state,” hundreds of demi-humans united of their pedophiliac designs on America’s kids.

The efforts to carry the instigators of the rebellion to account have likewise unfolded as leisure. “Opinion: January 6 Hearings May Be a Actual-Life Summer season Blockbuster,” learn a CNN headline in Could—the unspoken corollary being that if the hearings failed on the field workplace, they’d fail at their goal. (“Lol nobody is watching this,” the account of the Republican members of the Home Judiciary Committee tweeted because the hearings have been airing, making an attempt to recommend such a failure.)

The hearings didn’t fail, although; quite the opposite, the primary one was watched by some 20 million folks—rankings much like these earned by a Sunday Evening Soccer broadcast. And the success got here partly as a result of the January 6 committee so ably turned its findings into compelling TV. The committee summoned well-spoken and, in lots of instances, telegenic witnesses. It made a degree of reworking that day’s chaos right into a complete plot. Its manufacturing was so profitable that The New York Instances included the hearings on its record of 2022’s greatest TV exhibits.

The committee understood that for folks to care about January 6—for folks to take an curiosity within the biggest coup try in American historical past—the violence and treason needed to be translated into that common American language: present.

In September, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis organized for a bunch of individuals in search of asylum within the U.S. to board airplanes. They have been advised that housing, monetary help, and employment can be ready for them once they landed. As a substitute, the planes flew to Martha’s Winery, the place there was nothing ready for the confused vacationers besides a bunch of equally confused locals. However these locals gave the vacationers meals and shelter. Immigration attorneys got here to assist. Journalists obtained copies of the brochures that had been handed out to the asylum seekers, and knowledgeable the general public of the sequence of false guarantees by way of which human beings had been changed into props.

The send-them-to-the-Winery plan had been fueled by TV. After Texas Governor Greg Abbott started busing migrants to locations the place they’d supposedly grow to be a burden to Democrats, “transport migrants” grew to become an everyday matter of dialog on the morning present Fox & Associates, and Fox Information typically. The hosts stuffed their airtime joking concerning the conveyances that might be essential to ship folks to the Winery. The thought was repeated so steadily that, as typically occurs, the joke grew to become the plan, after which the plan grew to become the truth, after which the asylum seekers, determined and misled, have been despatched like Amazon Prime packages to a spot chosen as a result of Barack Obama holidays there.

And the producers of the entire thing, fairly than questioning the premise of their present after it did little apart from expose a neighborhood rallying to assist folks in want, as an alternative promised extra performances. Senator Ted Cruz—whose father, because it occurs, sought asylum within the U.S.—introduced that one other group of asylum seekers can be shipped to Joe Biden’s trip spot. (“Rehoboth Seaside, Delaware subsequent,” he stated.) Abbott continued busing migrants out of Texas—this time the drop-off location was in entrance of Vice President Kamala Harris’s Washington, D.C., residence. The Nationwide Republican Senatorial Committee, to not be outdone, introduced viewers participation to the present: A fundraising e-mail requested recipients the place Republican governors ought to “ship” migrants subsequent.

“The propagandist’s goal,” Aldous Huxley noticed, “is to make one set of individuals neglect that sure different units of individuals are human.” Donald Trump had a behavior of demeaning his opponents, en masse, as “vicious, horrible” folks. The photographs have solely grown extra hallucinatory. In September, Consultant Marjorie Taylor Greene advised a gathering of younger folks in Texas that her Democratic colleagues are “type of evening creatures, like witches and vampires and ghouls.”

The rhetoric could appear absurd, but it surely serves a goal. That is language designed to dehumanize. And it’s language that has gained traction. Final 12 months, the Public Faith Analysis Institute printed an evaluation of QAnon’s maintain over People. The group requested almost 20,000 survey respondents whether or not they agreed with the QAnon perception that “the federal government, media, and monetary worlds are managed by Devil-worshiping pedophiles.” Practically a sixth—16 %—stated they did.

“I’m a Actual Individual”

In his 1985 e book, Amusing Ourselves to Demise, the critic Neil Postman described a nation that was shedding itself to leisure. What Newton Minow had referred to as “an enormous wasteland” in 1961 had, by the Reagan period, led to what Postman identified as a “huge descent into triviality.” Postman noticed a public that confused authority with celeb, assessing politicians, non secular leaders, and educators in accordance to not their knowledge, however to their capacity to entertain. He feared that the confusion would proceed. He frightened that the excellence that knowledgeable all others—truth or fiction—can be obliterated within the haze.

In late 2022, The New York Instances revealed that George Santos, a newly elected Republican consultant from Lengthy Island, had invented or wildly inflated not simply his résumé (a well-known political sin) however his total biography. Santos had, in essence, run as a fictional character and received. His lies and obfuscations—about his training, his employment historical past, his charitable work, even his faith—have been surprising of their brazenness. They have been additionally met, by many, with a collective shrug. “Everybody fabricates their résumé,” certainly one of his constituents advised the Instances. One other vowed her continued assist: “He was by no means untruthful with me,” she stated. Their reactions are harking back to the Obama voter who defined to Politico, in 2016, why he can be switching his allegiances: “A minimum of Trump is enjoyable to look at.”

These are Postman’s fears in motion. They’re additionally Hannah Arendt’s. Finding out societies held within the sway of totalitarian dictators—the very actual dystopias of the mid-Twentieth century—Arendt concluded that the perfect topics of such rule should not the dedicated believers within the trigger. They’re as an alternative the individuals who come to consider in all the things and nothing in any respect: folks for whom the excellence between truth and fiction now not exists.

A republic requires residents; leisure requires solely an viewers. In 2020, a former well being official frightened aloud that “viewers will get bored with one other season of coronavirus.” The priority, it turned out, was warranted: People have struggled to make sense of a pandemic that refuses to evolve to a tidy narrative construction—digestible plots, cathartic conclusions.

Life within the metaverse brings an aching contradiction: We now have by no means been in a position to share a lot of ourselves. And, as research after research has proven, now we have by no means felt extra alone. Fictions, at their greatest, develop our capacity to know the world by way of different folks’s eyes. However fiction can flatten, too. Recall what number of People, within the grim depths of the pandemic, refused to know the sporting of masks as something however “advantage signaling”—the efficiency of a political view, fairly than a real public-health measure. Observe what number of pundits have dismissed well-documented tragedies—kids massacred at college, households separated by a callous state—because the work of “disaster actors.” In a functioning society, “I’m an actual particular person” goes with out saying. In ours, it’s a determined plea.

This could possibly be how we lose the plot. This could possibly be the somber finale of America: The Restricted Sequence. Or maybe it’s not too late for us to do what the denizens of the fictional dystopias couldn’t: lookup from the screens, seeing the world as it’s and each other as we’re. Be transported by our leisure however not sure by it.

“Are you not entertained?” Maximus, the hero of Gladiator, yells to the Roman throngs who deal with his ache as their present. We’d see one thing of ourselves in each the captive warrior and the group. We’d really feel his righteous fury. We’d acknowledge their enjoyable. We now have by no means been extra entertained. That’s our luxurious—and our burden.

This text seems within the March 2023 print version with the headline “We’re Already within the Metaverse.” Once you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

[ad_2]

No Comment! Be the first one.